THE LUCKY ONES MAY NOT HAVE REALIZED

they were dying. The casino was on fire, they might have

known that. But no flames were drawing near, thick smoke

wasn't pouring in through the vents or under the doors,

as was happening elsewhere in the MGM Grand hotel-casino

that Friday morning, November 21, 1980. Also, it was just

after 7 a.m.; they might have been asleep, still groggy.

They may have retained a semblance of calm, awaiting rescue.

But they were doomed anyway, doomed by the very thing that

made mass tourism possible in Las Vegas: air-conditioning.

It filtered out the smoke but pumped deadly carbon monoxide,

a silent killer, into their rooms.

The unlucky ones knew. Trapped in smoke-choked stairwells,

the doors automatically locked behind them in an ironic

fire-safety measure, they clawed their fingers bloody on

any millimeter of purchase that might pry open a way out;

news accounts mention the red handprints they left on the

walls. Others stumbled through corridors, lungs filling

with toxic smoke. At what moment did each of the victims

understand they were going to die--that whatever wealth

they'd amassed couldn't save them, nor their devout faith,

nor their worldly accomplishments? Imagining those awful

moments of realization can break your heart 20 years later.

|

|

Weary, some barely dressed, they were staggered by the event's

enormity.

The truly lucky ones, of course, were those who got out

alive, many injured--some badly--but gratefully alive. Some

jumped or slid down ropes. Some fled to the roof and were

choppered to the ground. Some were rescued by ladder. Some

bashed open their windows for the fresh air, raining glass

shards, televisions and hotel furniture to the ground. Some

remained safe in their rooms. Some crossed that threshold

of realization, knew absolutely that they were about to

die, but--lucky, lucky--did not.

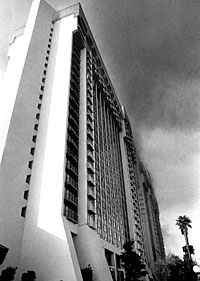

The enormity of it--the freakish extremity of it. That's

what strikes you in hindsight, how outsize everything about

the MGM fire was: the monster fireball, and the heedless

ferocity of its consumption; the dramatic tower of smoke,

said to be 2,000 feet high; the vast emotional panorama

experienced by the victims, survivors, rescuers, onlookers;

the sprawling, precedent-setting legal actions that followed;

and the death toll itself, 87, making it the second-worst

hotel fire in the nation's history.

Then again, maybe it's the small things that stand out.

The way a seemingly innocuous decision--to stay in the room

with one group of friends or go downstairs with another--would

have life-or-death implications for Perry Beshoar of Western

Springs, Illinois. Or the way a hundred twists of fate delivered

an MGM maintenance man into a 10th-floor corridor just in

time to stop Robert and Linda Boogren of Westland, Michigan,

from going into a stairwell ("Don't go down those stairs!

Those doors will lock behind you!"). Or the way Roger

Mack of Beaumont, Texas, wracked by the agony of two broken

legs after sliding down a construction rope, managed to

lift his head and croak, "How is my wife?," meaning

Delores, who'd gone first. (The answer would shatter his

heart, too.) Or the soot trails leading up the nostrils

of the dead. Or the way human memory balks and falters over

some details of the event, yet randomly inscribes others

so indelibly. Or the way so much devastation--a 26-story

box of sheer human misery--can flare from an epicenter as

small as a wire.

TOM HUME WASN'T WORRIED. HELL, PEOPLE PROBably scream in

hotel hallways all the time in Vegas--it's Vegas. Particularly

in one of the city's flagship hotels (today, it's Bally's).

Those noisy bastards undoubtedly won a bunch or lost a lot

or drank too much. "Don't pay attention to those people,"

the Cincinnati Reds pitcher told his wife as they drowsed

in bed. "This is Las Vegas. There's nothing to be alarmed

about." He and his teammate, Bill Bonham, and their

wives had stopped in town on their way to Tucson to play

in a March of Dimes celebrity golf tournament; they were

on the 24th floor, two from the top.

"Then I went over to the window and saw smoke coming

up the side of the building," he says by phone from

an Indiana fishing trip.

It had started downstairs, in an attic above a kitchen

that served several restaurants. Faulty wiring. It smoldered

for a few hours, unsuspected by employees or guests, flaring

up just after 7 a.m., quickly bursting into violent life,

unchecked by sprinklers (the casino had none), propelled

by its own fury, racing into the casino, killing people,

scorching slot machines, singeing lives.

It didn't seem that big when the firemen of Station 11,

then located across Flamingo Road, arrived shortly after

the 7:19 call. No smoke or signs of fire outside. Routine

grease fire, probably.

Tourist Kurt Schlueter, a firefighter with the Western

Springs, Illinois, fire department, had just ordered coffee

in the coffee shop downstairs with a co-worker, Dave Beshoar,

and Beshoar's brother, Perry. Their friends David Potter

and William Gerbosi, also firemen, were still upstairs getting

dressed. Perry almost stayed in the room, opting at the

last minute to come downstairs. "A security guard came

up to us and said, 'We have to evacuate the restaurant,

there's a small fire next door,'" Schlueter says by

phone from Illinois. "We looked around the corner and

we could see the fire and it didn't look that big."

He and Beshoar offered their firefighting services, but

the guard said the equipment was inaccessible. Instead,

they helped herd other patrons out.

Some gamblers weren't ready to leave on account of a stupid

kitchen fire. One blackjack dealer told reporters, "I

was dealing to two middle-aged ladies and noticed the smoke

first. The ladies wanted to keep playing, but I said, 'No

way.' They were kind of upset when I told them they had

to leave." Entering the casino, the firemen from Station

11 still thought it was nothing out of the ordinary. Then,

with a terrible swiftness the firefighters would later compare

to high-speed photography, a ball of fire raged from The

Deli restaurant, whooshing along the combustible casino

ceiling, consuming everything in its way. Someone said,

"Get the drop boxes!" A dealer shouted back, "Screw

the boxes, get yourself out of here!" In the kitchen,

two cooks ducked into a freezer. The smoke and heat pushed

Schlueter and his friends out the door. Standing outside,

watching the flames lick out of the building as the firemen

dragged their hoses into position, the three wondered what

had become of Potter and Gerbosi.

The casino area was in flames, and because the MGM was

built in 1973--"the golden era of plastics," one

lawyer would later say--deadly fumes quickly rose through

the ventilation systems and stairwells.

Up on the 24th floor, Tom Hume pulled on his pants and

stepped into the hallway. Smoke everywhere. He banged on

Bonham's door, then pounded warnings on other doors before

hurrying to his room to get dressed. He yanked on his boots--no

socks, he remembers--while his wife got into her warmup

suit and they headed down the stairwell. He remained calm,

he says.

"Billy and his wife were in front of us, and Billy

was helping these ladies carry their suitcases down the

stairs, and I was like, 'Billy, let's go!'" About 10

floors down, the smoke got to be too much and they decided

to head for the roof.

On the 16th floor, Marv and Carol Schatzman were getting

ready to return to St. Louis that morning; they had an 8:15

flight. Marv was heading down to check out. He paid no mind

to the haze in the hallway, didn't even think about it.

A bellboy ran up to him and asked in broken English to use

the phone in the Schatzman's room. But the phone wasn't

working and the bellboy blurted, "I think the hotel

is on fire." They looked out the window saw the fire

engines. They'd heard no alarm.

Again, the fortuitous twist of fate: Had Marv gotten on

the elevator, it would have delivered him to the fire. Now,

instead, they headed for the stairwell. Along the way, Carol

pounded on doors, shouting "Smoke! Smoke!" instead

of "Fire!" because she'd heard that if you shouted

"Fire" and it turned out there wasn't one, you

could go to jail.

Civilian, police and military choppers joined the lengthy

rescue operation.

WHEN WE GOT OFF the freeway we could see flames coming out

of the front lobby," recalls Metro Officer Tim Montoya,

who arrived about 20 minutes after the alert. "It was

just enormous." He was assigned to the perimeter, trying

to keep the growing crowd of gawkers at bay. High above,

MGM guests leaned from their windows, screaming. "I

felt a sense of helplessness," he says. "You feared

for their lives because there was no way to get them out.

Most people in a fire die from the smoke, and it was obvious

the smoke was traveling straight up the stairwells. You

felt that the people you were looking at were not going

to be alive much longer. The smoke was coming out of their

rooms behind them."

Patrolman Tom Thowsen of the canine unit was there with

his dog, Izzy, also on the perimeter. While the fire was

still burning, word came down that there might be looters

inside, scooping up chips and money. Thowsen was among those

ordered to check it out. "We start up the steps going

into this place, and there was a firefighter there with

an air pack on. He said, 'What're you doing?' We said, 'We've

been told there are looters in there.' And he said, 'It's

full of toxic fumes and smoke! You won't be able to breathe!'

And we realized there was probably no one in there looting."

Mel Larson, then a vice president of Circus Circus and

an accomplished helicopter pilot (he and his wife owned

Action Helicopter Services), had seen the smoke from his

home and scrambled his pilots to help. "People were

hanging out of windows, motioning for us to come get them,"

Larson says. No way he could swing the chopper that close,

of course, so he had to look at their panicked faces and

know there was nothing he could do for them. Instead, he

headed for the roof, to help survivors gathered there.

Some people jumped; Kurt Schlueter would never forget that

sight. One witness told the Las Vegas Sun that he'd seen

a heavyset man shimmying down a rope of knotted sheets before

plummeting three stories. Moments later, a woman tried the

same rope, falling too. Inside, many guests simply waited

in their rooms, some lying on the floor with wet towels

over their heads, others smashing their windows or opening

the balcony doors. A woman in one room called Las Vegas

Sun reporter Mary Manning, looking for details on the fire;

she was so nervous, she confessed to Manning, that she'd

lit a cigarette. Roger and Delores Mack found a construction

rope knotted to a balcony on the ninth floor. In a decisive

moment, Delores, perhaps thinking it her only chance, went

first; she'd slid just a few feet before she fell, landing

on a second-story roof, crushing her head. Roger slid after

her, breaking both legs.

DOWN WASN'T RIGHT. Down was, in fact, very, very wrong.

So Tom Hume's party headed up the stairwell through the

choking fumes, a dispiriting prospect. "I remember

my wife sitting down," Hume says, "sitting on

the stairs, and she said, 'I can't go any further.' And

I took her warmup top and stuck it over her face and I said,

'You go until I say stop! And you don't stop until I tell

you to!' And she said, 'Yeah, but there's nobody there.

There's nowhere to go.' And I said, 'Let's go!'"

The Schatzmans, descending their stairwell from the 16th

floor, ran into a crush of people around the ninth, some

barely roused from bed and still half-dressed. "More

people kept getting in and there was no air and you couldn't

hardly see and you could hardly breathe," Marv says

from the couple's St. Louis-area home. "They said the

fire was down here and we had to go back up."

Up was hardly better. The smoke was blinding now, strangling.

People were succumbing to it, flopping onto the stairs or

sitting there, wheezing to catch a breath or just giving

up. Others, some breathing heavily through wet towels, continued

upward. The Schatzmans, nearly overcome, were reduced to

crawling blindly through the fumes. "When you inhale

smoke it makes your extremities very weak," Carol says.

"A lot of people were sitting down because they had

given up and we had to crawl over them."

There was no screaming, Carol wrote in an account of their

adventures she typed up when they returned to St. Louis.

No one could breathe enough to scream. There was no panic.

About the 24th floor, I knew we were going to die. She had

arrived at that terrible moment of realization, the sure,

sudden awareness that she was going to die a grim suffocating

death in a damn stairwell in Las Vegas. Still, they retained

their humanity. Marv took a woman's hand, tried to pull

her upward. "And in all the ... I guess ... the action,"

he recalls, his voice faltering, "I lost the hand.

And I know she didn't get out." Along with those strong

enough to continue on, the Schatzmans kept crawling toward

the roof, hoisting themselves along on the handrail, unsure

what would await them up top, if they ever got there. Locked

door? Unlocked?

A wet towel helped ward off the fumes from burning plastic.

FIREFIGHTERS MOVED up the stairwells, fanning out to look

for survivors. Engineer Bill Trelease was part of the rescue

effort, busting down doors and performing CPR--when it wasn't

too late. "One gal, she'd been by the elevator, pushing

the button," he recalls. "She died there, and

you could see her fingerprints going down the soot on the

wall; her arm was still outstretched when we found her."

In a stairwell, he came across several bodies piled on top

of each other, as if stacked that way. Breaking through

one door, he found an elderly couple, kneeling in prayer

at the foot of their bed. Dead. At wrenching moments like

that, a firefighter's mind constricts around a narrow cluster

of priorities that amount to this: save the living.

GROPING UPWARD, THE SCHATZMANS EXPECTED TO encounter parties

of people coming back down, telling them the door was locked.

Carol knew she couldn't maintain hope in the face of that.

Memory is mystifying, erratic, particularly when it's forged

in the literal crucible of a tragedy like the MGM fire.

Was the young man who leaned over the top of the stairwell,

shouting that the rooftop door was open, a shirtless 20-year-old,

as Carol noted in her written account, or a 16-year-old

in his underpants, as she remembers now? All that matters

is that he had the guts to duck back into the smoke-filled

stairway and let the others know that safety awaited. Then

we saw the sky through the open door, Carol wrote. My God,

it was heaven!

SOME NEWS ACCOUNTS FROM THE TIME DESCRIBE A full-tilt,

fall-of-Saigon panic on the roof, with men pulling women

out of rescue craft to secure themselves a seat, and a crowd

surging against a helicopter, shoving it perilously close

to the edge. Those up there say it wasn't quite that bad,

although firefighter Bill Trelease remembers it as akin

to "an LZ in Vietnam." Soot-stained and gasping,

the survivors were frantic, "trying to hang on the

skids, or stand on the skids" of the several choppers,

Mel Larson says, and others say people were clutching up

at the aircraft before they could land, sometimes impeding

the pilots or coming dangerously close to the tail rotors.

But for the most part, order prevailed, despite some folks'

fear that the roof could collapse at any moment into what

they imagined must be a roaring inferno below.

This being an earlier era of technology, the roof didn't

bristle with satellite dishes, aside from a few antennae

that had to be broken off to make way for the choppers.

Extra helicopters--commercial, official, construction--arrived

to help ferry down the evacuees. Military pilots engaged

in Red Flag exercises at Nellis were dispatched to assist.

All those rotors helped dispel smoke on the roof, although

the jumbo military choppers had an unforeseen side effect:

They pushed smoke back into the building, where firefighters

were assisting people. "You'd hear them coming and

you knew you were screwed," Trelease says. "Within

30 seconds the smoke would again be so thick you couldn't

see your hand in front of your face." Guests whom the

firemen had managed to settle down would freak again.

Safely on the roof, Tom Hume somehow managed to dump out

a pocketful of change. With the eerie calm that sometimes

descends on participants in a disaster, he bent down and

carefully picked it all up. His wife was rattled, but he

knew, he just knew, that they'd survive.

We formed lines to wait for the helicopters, Carol Schatzman

wrote. I began to think we might have a chance. Women went

first. A black man put his wife in a helicopter and turned

away. A man was in line behind him trying to get on, and

he said, "Man, we want the women to be safe, don't

we?" and the man said, "Yes, forgive me."

It made me cry even more.

The Schatzmans watched one man escort his wife safely to

the roof, then dash back into the stairwell to find her

sister, who had been right behind them. Neither came, Carol

wrote.

Hume and Bonham put their wives on the choppers, then waited

their turn. Hume estimates that they were among the last

men off the roof, but here his memory blanks: "I don't

remember getting on the helicopter and flying to the ground,"

he says. "I know we landed in a parking lot."

The Schatzmans were separated when Carol was choppered

down with three women in nightgowns, their bare feet bleeding.

Carol was a mess. "Our faces were black," she

says. "I have blond hair and it was green."

Forty minutes after Carol came down, Marv followed, seemingly

in bad shape. The medical personnel thought he'd had a heart

attack; his lips were blue from inhaling the soot. He was

taken by ambulance to Desert Springs Hospital for a battery

of tests. Carol sat in the waiting room with a Mexican woman

who didn't speak English. Bonded by tragedy, they said the

Rosary and comforted each other. Someone asked Carol if

she wanted a drink and was taken aback when she answered,

"Brandy." I meant coffee or orange juice! the

woman replied. "The doctor turned around and said,

'Oh, hell, I've got some Scotch in my desk,' so he went

and got it. No one drank it, we just sat and looked at it,

but it made us feel good to know it was there."

Survivors wound up all over the place. Some went to the

Barbary Coast, where shift manager Steve Morrill closed

the tables for three hours and converted the lounge into

a makeshift medical area. ("When I walked in the door,"

Barbary Coast owner Michael Gaughan recalls, "Steve

came running toward me, panicked, worried about whether

or not he did the right thing. Of course, I told him he

did.") The Rev. Billy Graham, in town for four days

of evangelism, "walked among the dazed and crying tourists

at the still burning hotel, helping comfort them,"

according to one newspaper. Like most evacuees, Kurt Schlueter

and his companions wound up at the Convention Center, amid

the dazed, haphazardly dressed multitude (one woman was

in a nightgown and mink stole, all she managed to throw

on before escaping). "We spent the rest of the day

looking for our two buddies," he says, his voice breaking,

two decades later. A friend from another hotel picked them

up and, with fading hope, they checked out hospitals, the

morgue. "Nobody could give us a straight answer about

where they were," Schlueter says. "There were

so many conflicting stories."

Until: "We finally found them in a portable morgue."

The fire burst from the kitchen in a huge cinematic fireball.

LAS VEGANS RALLIED QUICKLY. RESIDENTS BROUGHT clothing and

blankets to cover the survivors. Carol Schatzman remembers

several stores letting people charge clothing with only

a name and address. Some who came to gawk found themselves

pitching in. Hotels offered free or cut-rate rooms, sent

food and supplies to the staging areas; the Landmark reportedly

had security guards running to nearby pharmacies to fetch

medications for the survivors. The Rev. Billy Graham declared

that he'd never seen a community pull together like this.

Not everyone behaved as Graham would have wanted, however.

Several people were arrested for interfering with rescue

units, and, according to news reports, before the fire was

even out, an MGM security guard was busted at a nearby casino

for gambling with wet, burnt bills he presumably scooped

from tables as he escaped.

Released from the hospital, the Schatzmans were shuttled

to the Convention Center, where the living were tallied.

"We were amazed at how many people were still alive,

to tell you the truth," Carol says. Later, a cabbie

gave them a free ride to the airport; they were still in

the clothes they'd put on that morning, now soot-ruined

(some people in the airport broke into sympathetic tears).

At long last, they returned home. Their belongings followed

a month later, rifled-through and reeking of smoke. Continue

Continue

You

must stay on a fully sprinklered hotel for your safety

Back to MGM Fire Case

|